After a quick introduction to SRE in the previous blogpost, lets step into the principles as shared by Google in their book. Wikipedia defines Reliability as the probability that a system will produce correct outputs up to some given time “t”. Reliability is enhanced by features that help to avoid, detect and repair hardware faults. A reliable system does not silently continue and deliver results that include corrupted data. Instead, it detects and, if possible, corrects the corruption. Reliability can be characterized in terms of mean time between failures (MTBF), with reliability = exp(-t/MTBF).

While getting reliability to 100% appears to be ideal, there is cost involved. SRE outlines the following principles that can help achieve desired reliability level by balancing resiliency with cost. This blogpost will briefly cover each principle and help us appreciate SRE practices that will be covered next.

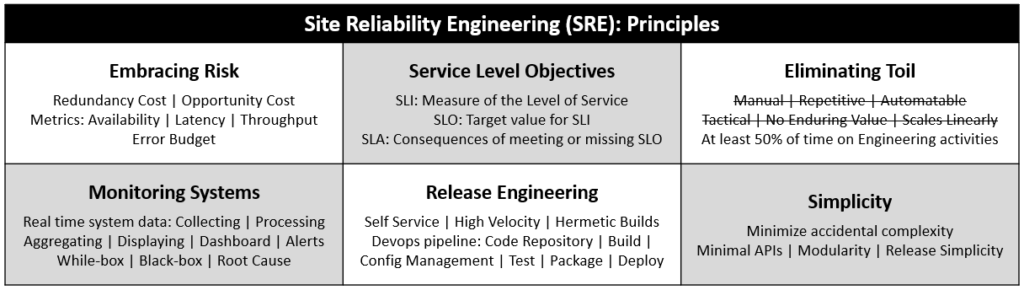

- Embracing Risk

- Service Level Objectives

- Eliminating Toil

- Monitoring Systems

- Release Engineering

- Simplicity

Embracing Risk:

SRE seeks to balance the risk of unavailability with the goals of rapid innovation and efficient service operations, so that users’ overall happiness – with features, service, and performance – is optimized. Efforts to increase reliability beyond a certain point will exponentially increase recurring costs making it economically worse for a service and its users. Cost of improving reliability can be categorized into two buckets, both of them are invisible to end users but essential to avoid disruptions rather than building new features:

- The cost of redundant machine / compute resources.

- The opportunity cost when engineers are allocated to improve reliability.

In SRE, service reliability is managed by managing risk. The goal is to explicitly align the risk taken by a given service with the risk the business is willing to bear and strive to make a service reliable enough, but no more reliable than it needs to be. To achieve this, a set of Service Level Objectives need to be defined and this will be covered in the next principle.

Before that, another key concept is Error Budgets. As we embrace risk this way, tensions will arise between Product Development and SRE teams as they are usually evaluated on different metrics. An error budget aligns incentives and emphasizes joint ownership between SRE and product development. Error budgets make it easier to decide the rate of releases and to effectively defuse discussions about outages with stakeholders, and allows multiple teams to reach the same conclusion about production risk without rancor.

Service Level Objectives:

To manage a service, we first need to express its important behaviors quantitatively and then define the level of service that will be delivered. Three important terminologies that help achieve this are:

- Service Level Indicator (SLI): a carefully defined quantitative measure of some aspect of the level of service that is provided. Examples – request latency, error rate, system throughput, availability, durability.

- Service Level Objective (SLO): a target value or range of values for a service level that is measured by an SLI. Example – 99% of Get RPC calls will complete in less than 100 ms.

- Service Level Agreement (SLA): an explicit or implicit contract with your users that includes consequences of meeting (or missing) the SLOs they contain. SLAs usually have financial implication for violating SLO.

Eliminating Toil:

Toil is the kind of work tied to running a production service that tends to be manual, repetitive, automatable, tactical, devoid of enduring value, and that scales linearly as a service grows. SRE’s goal is to eliminate toil so that they can spend time on long-term engineering project work. Typically 50% of each SRE’s time should be spent on engineering project work that will either reduce future toil or add service features.

Monitoring Systems:

Monitoring includes collecting, processing, aggregating and displaying real-time quantitative data about a system, such as query counts and types, error counts and types, processing times and server lifetimes. Effective monitoring helps proactively avoid failures and involves alerting, building dashboards, analyzing long term trends and root cause analysis. Monitoring can either be:

· White-box that is based on metrics exposed by the internals of the system, including logs, interfaces like JVM Profiling Interface or an HTTP handler that emits internal statistics.

· Black-box that involves testing externally visible behavior as a user would see it.

Release Engineering:

When equipped with the right tools, proper automation, and well-defined policies, developers and SREs shouldn’t have to worry about releasing software. Releases can be as painless as simply pressing a button and Release Engineers help achieve this using devops pipeline that includes source code repository, build rules for compilation, configuration management, test integration, packaging and deployment.

Release engineering is guided by an engineering and service philosophy that’s expressed through four major principles:

- Self-Service Model: Tools and process that allows product development teams to control and run their own release processes and achieve high release velocity.

- High velocity: Frequent releases that result in fewer changes between versions.

- Hermetic Builds: Self-contained builds that must not rely on services that are external to the build environment.

- Enforcement of Policies and Procedures

Simplicity:

Software simplicity is a prerequisite to reliability. With an eye towards minimizing accidental complexity, SRE teams should:

· Push back when accidental complexity is introduced into the systems for which they are responsible.

· Constantly strive to eliminate complexity in systems they onboard and for which they assume operational responsibility