I began 2022 with Adam Grant‘s latest book “Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know“. This book is an invitation to let go of knowledge and opinions that are no longer serving us well, and to anchor our sense of self in flexibility rather than consistency. This also means abandoning some of our most treasured tools and some of the most cherished parts of our identity.

The key is “rethinking” – adopting mental flexibility to let go of our long held assumptions and have the courage to challenge our self-beliefs that might have led to success in the past but no longer relevant for the future. As an example, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced organizations to rethink the value of co-located teams working in close physical proximity all the time to deliver projects. Instead, all organizations are now exploring the flexibility offered by remote work for people to balance their professional and personal goals better. Contrary to long held belief, many remote teams have been more productive working from home as they repurposed unproductive time spent on activities like the office commute. It does not mean that remote work will be the better option forever, we are certain to encounter new challenges and we need to rethink again to address them.

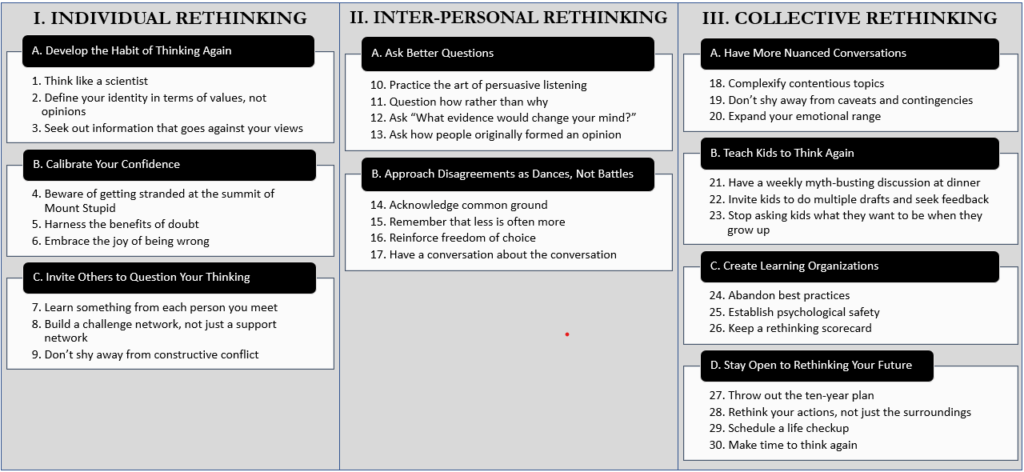

This book makes a case for rethinking at three levels – Individual, Interpersonal and Collective.

Individual Rethinking – Updating our own views:

- A Preacher, a Prosecutor, a Politician and a Scientist walk into your mind: Our assumptions and beliefs often drive us towards two biases – Confirmation bias (seeing what we expect to see) and Desirability bias (seeing what we want to see). These biases contort our intelligence into a weapon against the truth. We find reasons to preach our beliefs more deeply, prosecute our case more passionately and ride the tidal wave of our political party. The tragedy is that we are usually unaware of the resulting flaws in our thinking. To avoid this conundrum, we should think like a scientist, and NOT like a preacher or a prosecutor or a politician. Thinking like a scientist requires searching for reasons why we might be wrong and revising our views based on what we learn.

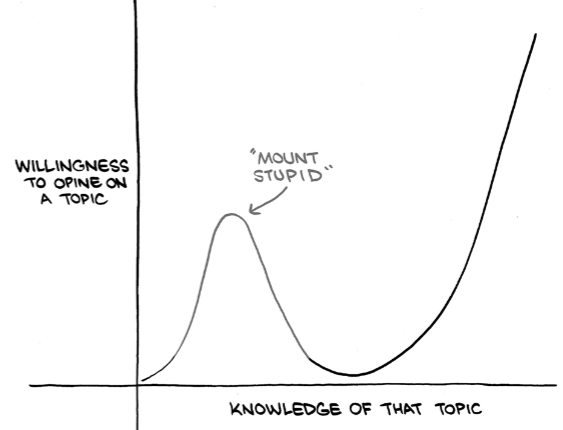

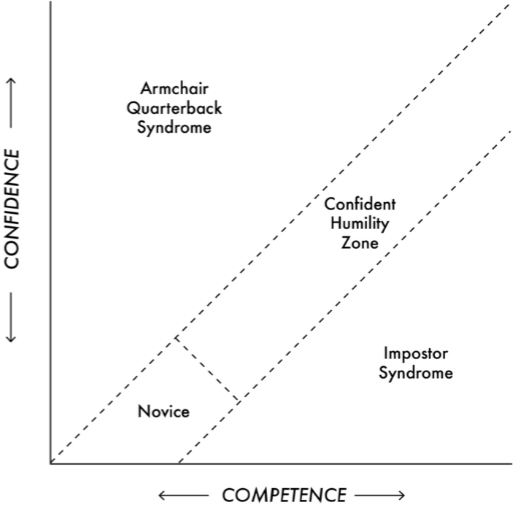

- The Armchair Quarterback and the Imposter – Finding the sweetspot of confidence: Knowledge on a topic leads to both competence and confidence, the balance between both of them will determine our personality. We need to be careful when we progress from being a novice to an amateur in a skill as this is the stage when we tend to become overconfident reaching the summit of what is called “Mount Stupid“. As we progress further towards becoming a professional, we realize there is a lot more to learn and usually become more humble. We should strive to reach a state of “Confident Humility” – having faith in our capability while appreciating that we may not have the right solution or even be addressing the right problem. This gives us enough doubt to reexamine our old knowledge and enough confidence to pursue new insights.

- The Joy of being Wrong: Most of us are accustomed to defining ourselves in terms of our beliefs, ideas and ideologies. This can become a problem when it prevents us from changing our minds as the world changes and knowledge evolves. Our opinions become so sacred that we grow hostile to the mere thought of being wrong, and the totalitarian ego leaps in to silence counterarguments, squash contrary evidence and close the door on learning. Instead, it is better we define ourselves by our values. Values are our core principles in life – like respect, fairness, empathy, trust, courage, etc. Basing our identity on these kinds of principles enables us to remain open-minded and enjoy instances when were go wrong as opportunities to learn.

- The Good Fight Club – The psychology of constructive conflict: High performing groups thrive on task conflict to bring the collective best by challenging different views with mutual respect (so that it does not slip into relationship conflict).

Interpersonal Rethinking – Opening other people’s minds:

- Dance with Foes – How to win debates and influence people: When we want to convince others to rethink their opinions, we frequently take an adversarial approach that effectively shuts them down or rile them up instead of opening their minds. They play defense by putting up a shield, play offense by preaching their perspectives and prosecuting ours, or play politics by telling us what we want to hear without changing what they actually think. The better approach will be a more collaborative one, where we show more humility and curiosity, and invite other to think more like scientists. A good debate is not a war, it is more like a dance that has not been choreographed, negotiated with a partner who has a different set of steps in mind. To accomplish this, expert negotiators use a few techniques: acknowledging common ground, presenting fewer reasons to support their case and expressing curiosity with intriguing questions.

- Bad Blood on the Diamond – Diminishing prejudice by destabilizing stereotypes: In every human society, people are motivated to seek belonging and status. Identifying with a group checks both boxes at the same time: we become part of a tribe and we take pride when our tribe wins. This leads to rivalries between tribes (teams) that are typically geographically close, compete regularly and are evenly matched. Some examples in sports is rivalry between India and Pakistan on cricket or between the Yankees and Red Sox in baseball. To reinforce the rivalry, stereotypes are formed and for both mental and social reasons it is hard to undo them. Some of the ways to overcome stereotypes are: come up with shared identify using commonalities (overview effect), humanizing the team and focusing on an individual to explain irrationality of the stereotype.

- Vaccine Whisperers and Mild Mannered Interrogators – How the right kind of listening motivates people to change: People with unhealthy additions or unscientific beliefs are usually aware of their fallacies. If we try to persuade them to make a change, we evoke resistance and they are less likely to change. We can rarely motivate someone else to change, instead we are better off helping them find their own motivation to change. “Motivational Interviewing” is a practice that can help with this. Motivational interviewing starts with an attitude of humility and curiosity. Our role is to hold up a mirror so they can see themselves more clearly, empower them to examine their beliefs and behaviors that can activate a rethinking cycle. Three key techniques for motivational interviewing are: asking open-ended questions, engaging in reflective listening and affirming the person’s desire and ability to change.

Collective Rethinking – Creating communities of lifelong learners:

- Charged Conversations – Depolarizing our divided discussions: As humans, we have the tendency to seek clarity and closure by simplifying complex continuum into two categories. This is called binary bias. While democratization of information through internet was expected to expose us to different views and help us make informed rational decisions, binary bias has instead led to a more polarized world. To overcome binary bias, a good starting point is to become aware of the range of perspectives across a given spectrum and articulate the complexity instead of simplifying it. Some techniques to convey complexity are: including caveats, highlighting contingencies and expressing mixed emotions.

- Rewriting the Textbook – Teaching students to question knowledge: With so much emphasis placed on imparting knowledge and building confidence, many teachers don’t do enough to encourage students to questions themselves and one another. It is important to instill intellectual humility, disseminate doubt and cultivate curiosity to develop students of today into confidently humble experts in their respective domains tomorrow.

- That’s Not the Way We Have Always Done it – Building cultures of learning at work: Rethinking is more likely to happen in a learning culture, where people strive to know what they don’t know, doubt their existing practices and stay curious. To achieve this “Psychological Safety” – fostering a climate of respect, trust and openness in which people can raise concerns and suggestions without fear of reprise – is essential. In performance cultures, the emphasis on results often undermines psychological safety. When we see people get punished for failures and mistakes, we become worried about proving our competence and protecting our careers. While many organizations strive to build high performance cultures with the right intention, care should be taken to ensure psychological safety in parallel to promote learning culture. Psychological safety should be combined with process accountability to create a learning zone where people feel free to experiment and to poke holes in one another’s experiments in service of making them better.

Adam Grant concludes by making a case for regularly reconsidering our best-laid career and life plans to escape tunnel vision that hampers our growth. He leaves us with specific actions for impact, which are his top thirty practical takeaways for working on our rethinking skills. I will conclude this blogpost with these takeaways.